Nefyn Lobster and Mackerel Fishing

1953

It was an early July morning on Nefyn beach. My father woke me up around four

o’clock when it was still dark. After a quick breakfast, we walked briskly on to St

David’s Road, along Ty’n Pwll Lane, across the field, and down the cliff path on to the

beach. We were heading out to sea for mackerel, and to fish his lobster pots. It was

very quiet and calm, and there was no one else around – a perfect Nefyn beach summer

morning. The earliest lights of dawn were just breaking over the Rival Mountains as we

rowed out in the old M155 boat to his motorboat. The tide was out, and the sea was flat

and glassy with not a ripple in sight anywhere on the surface. The stillness was broken

only when a pair of oystercatchers, disturbed by our presence, took off from a sandy area

in the nearby Creigiau Mawr rocks and with loud calls flew out towards Nefyn Point.

We circled the stern of the motorboat detaching the weather cover from the cleats on

its side. I was then able to clamber over the side into the motorboat and continue the

cover detachment while my father tied the rowboat to the mooring buoy. With the cover

now sufficiently removed, he climbed into the motorboat and opened the valve on the

tank beneath the front deck to allow petrol to flow into the engine. He also lifted a small

removable section of the bottom boards and opened the seacock for cooling water. It

was all very methodical. There was no wasting of time. He was obviously eager to get

to the lobster pots. While I folded the cover and stowed it under the deck, he proceeded

to fire up the old Stuart Marine engine with a couple of turns of the handle. The engine

roared nicely into life. He removed the handle so it was out of the way, and secured the

cover over the flywheel. I detached the mooring bridle chain from the anchor post on the

front deck and slipped it over the side as he eased the engine into gear. With a hand on

the tiller, he slowly guided the motorboat through the buoys in the mooring area and out

into the open sea in the direction of Bodeilias Point. He glanced over the side to ensure

the cooling water was pumping correctly through the engine and turned up the throttle.

Then we sat down on the either side of the rear deck, facing forward, and with the tiller

between us. We were on our way. I glanced back towards the beach and the cliff path.

They were still empty, void of any other persons – just as I like to remember it.

It was the summer of 1953, and I was nearly twelve years old. I had just completed my

first year at Pwllheli Grammar School. My father was trying to make a living fishing

out of Nefyn, and since the weather was nice and calm, he had asked me along on one of

his trips. Fishing was not a lucrative business, but it helped pay the bills. All the fish

caught were sold locally, and the prime catch in the summer months was lobster. They

sold for a couple of shillings a pound which was very good money in those days. The

lobsters were much more plentiful than they are now. But no one had yet conceived

the idea of expanding markets by shipping the lobsters in tankers to large cities and to

foreign countries. The market was restricted just to the immediate area. Lobsters were

not very popular amongst the local population because they were so expensive. We

rarely ate lobster ourselves, and only when it was caught in the rocks – more on that later.

All the lobsters were sold to English visitors, and to the surrounding hotels catering to

those visitors. They had to be supplied live, so the fishermen stored their lobsters in

keeping pots hidden amongst the mooring buoys, and delivered them to their customers

on an as-needed basis. Mackerel were much more popular with the local people, but they

only sold for a few pennies each. Nowadays whelks are the fishermen’s shellfish of

choice for making money, and they are exported in bulk to the Continent. Whelks were

present in most of the lobster pots we pulled up, but they were just thrown back in the

sea. They were viewed as large sea snails and no one had an appetite for them. Making

a living as a fisherman in Nefyn in the 1950’s then was not an easy task, and it was hard

dangerous work. Lobster pots were constantly in need of upkeep and repair, and were

often lost in strong gales. All the boys in our family went along to help Dad with his

fishing at one time or another, but only when he deemed the weather satisfactory. A few

years earlier he had been in partnership with another Nefyn fisherman Dick Jones (Dicw),

but they decided to go their separate ways. How my father managed fishing on his own,

and in more difficult weather conditions, I shall never know. But manage he did.

He had a total of around thirty lobster pots spread along the coast from Gorllwyn to

Nefyn Point. His routine was to fish the furthest lobster pot first, and slowly work back

towards home. So on that early morning in July 1953 we were on our way down to

Gorllwyn, where the Rival Mountain falls into the sea around three miles down the coast.

We had to stop on the way to pull up a long-line he had set the previous afternoon. This

was a line approximately thirty yards long with fifty, periodically placed hooks along its

length with a small anchor at each end. The hooks were baited with lugworms or

mackerel strips. The function of the long-line was to catch dogfish and skate as bait for

the lobster pots. The dogfish has a very tough outer skin, and thornback skate has a very

bony inner body making them both excellent long lasting bait in the pots. It took us

around ten minutes to reach the long-line located just to the northeast of the mooring

area. As I steered the boat alongside, my father grabbed the buoy and proceeded to pull

the line in. A long-line of this kind has to be handled carefully not only because of the

large number of hooks but also because of the type of fish caught. The dogfish can

inflict a nasty bite, and its skin is not only tough but also rough and coarse like

sandpaper. Its lashing tail can deeply lacerate the wrist as the dogfish is held by the back

of the head to remove the hook. The thornback skate likewise has a backbone and tail

with long protruding barbs, and it also has to be carefully handled. It is a flatfish and its

mouth is on the underside. It does not have sharp teeth, and so in contrast to the dogfish

the safest way to remove a hook from a skate is to hold it by the lower lip. Keeping

hands away from the back and tail is a must. To avoid the possibility of any such

accidents, especially from the hooks, my father had a special wooden board into which

he could easily and securely clip the empty hooks as the long-line came on board. I

grabbed the wooden board from its usual location beneath the deck, and held it nearby.

This allowed him to use both hands to unhook the fish, drop them in the bait box, and

clip the hooks one at a time on to the board. On that particular morning, we caught five

two-feet long dogfish and one thornback skate.

After temporarily storing the long-line and anchors, we continued on our way towards

Gorllwyn. The trip down there took around an hour, and it gave us time to fish for

mackerel and to prepare the bait for the pots. I opened a small hatch beneath the rear

deck and pulled out two spinner hand-lines. We always used plain old hand-lines since

rods, reels, poles etc only got in everyone’s way. I carefully lowered the hand-lines

off the wooden winders into the water and tied each line to a cleat on either side of the

boat. We used the spinners to troll slowly along for mackerel. We hit mackerel almost

as soon as the lines were in the water, and I pulled in two nice fish, one on each line.

These were the small shoal mackerel typically around nine inches long. As soon as

the lines were back in the water, we hit another two fish. Catching that many in quick

succession implied we were over a mackerel shoal, and we had an alternative fishing

procedure for those circumstances. We immediately stopped the boat, pulled in the two

spinners, and replaced them with hand-lines with eight feathered hooks. If the boat was

still positioned over the shoal, then the fishing became really hectic and exciting. The

procedure was to jig the hand-lines up and down at different depths until the feathered

hooks were within the shoal. And, believe me, you knew exactly when that happened.

The line experienced multiple hits, was pulled in different directions, and felt as if it was

floating and weightless. As the line was pulled back into the boat it regained weight, but

it was a weight much greater than that associated with a single fish. My father took to

fishing one of the feathered lines while I fished the other. We started pulling mackerel

into the boat four to six at a time. We quickly established a routine of one person pulling

in a line and carefully holding it while the other person removed the fish off the hooks,

and then vise-versa. We caught around eighty fish in about half an hour before the

shoal moved on, and the frantic activity came to an abrupt end. Then back to trolling

with the spinners, and continuing on our way towards Gorllwyn.

The mackerel were very plentiful that summer morning and we stopped two more times

before reaching our destination. We pulled in approximately one hundred and thirty

fish, but we unfortunately lost one of the feathered lines in the process. Tope (pigwd)

always accompany those mackerel shoals. They are four-feet long, bluish-grey members

of the shark family who follow the shoal and feed on the mackerel. The first sign

indicating the presence of tope was when they accompany the mackerel caught on the

line to the surface as it was pulled in. We would keep a sharp lookout for tope when

jigging with feathers, and if we saw any, we would quickly pull in the lines and move to

fish in another area. There was no warning on that particular morning, just bang and the

line was gone – feathered hooks, line and sinker. It was not a major loss. We did not

have an expensive lead weight just a grooved stone, and the feathered hooks were easily

replaced with a visit to my grandmother’s chickens in the Fron.

As we traveled further down along the coast, my father proceeded to gut and cut up all

the dogfish and skate. This is the time when herring gulls suddenly appeared out of

nowhere and flew excitedly around the bow of the boat near the front deck where he

was working. He carefully wrapped the individual pieces in small sections of fine wire

netting (chicken wire), which were then ready for installation in the pots. The dogfish

and skate provided enough bait for around fifteen pots. He then also wrapped together

three mackerel at a time in wire netting for an additional group of five. The wire netting

helped keep the bait together to prolong its effectiveness. It was deemed essential for

the mackerel bait, which tended to disintegrate and turn mushy very quickly in the pot.

Dad indicated that one of the herring gulls would land on the boat quite often when he

was fishing alone. He indicated it had a bad leg, and he was not sure if it was present.

He threw a few pieces of mackerel on to the front deck, and then stepped back. One

of the gulls landed bravely on the deck, and sure enough it had a pronounced limp. It

nervously ate all the pieces of mackerel and then took off. Then the gulls all vanished as

soon as he cleaned and washed off the deck.

As we approached Carreg y Llam and Gorllwyn, the rays from the sun were starting

to filter over the Rival Mountains making Nant Gwrtheyrn and surrounding mountains

scenery even more spectacular. There is nothing comparable to that view from a half-

a-mile out at sea on a calm morning as the sun is rising. Not many Nefyn residents

have ever seen it, only that small fraction of the population with access to boats. Those

people appreciate the plaque in memory of fisherman Gwilym Shop Newydd on one of

the Nefyn cliff-path benches. It is inscribed eloquently in Welsh with the words.

“Caf fwrw angor yn y fan,

A gweld yr Eifl a Charreg Llam”

Translated for the benefit of the English-only locals, it reads with a minor rhyming

modification

“I can drop anchor in a tick-tock,

And view the Rivals and Bird Rock”

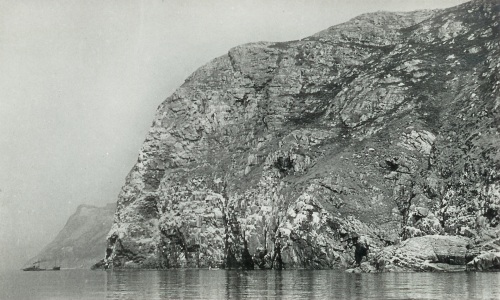

Bird Rock with Gorllwyn in the background. A coaster is waiting to load granite from the Carreg y Llam Quarry. The Llech Lydan rock is on the lower right.

(Click photo to enlarge)

A small coaster was anchored in the middle of Porth Nant Bay waiting for the tide to

come in so it could pull up alongside the Carreg y Llam Quarry pier for granite. We

passed the coaster on its seaward side. The crewmen were still asleep apparently since

there was no activity on board. We spotted our furthest green and yellow lobster pot

buoy just off the face of Gorllwyn. I think my father adopted those particular colours

when my elder brother Mike passed the eleven-plus examination to enter Pwllheli

Grammar School. Myself, and my young brother Terry, followed a few years later.

Green and yellow was the official school colours, and Dad painted all his rowing boats,

his motorboat, and his lobster pot buoys those same colors. All the schoolboys though,

us included, detested those green blazers we had to wear every day to school. With

the sea nice and calm, I had no difficulties guiding the boat alongside so he could grab

the buoy. I slapped the engine into neutral as soon as he had the buoy in hand to avoid

getting the pot rope tangled in the propeller. I recall that happening on one occasion,

and what a palaver!! We had to lift the rudder off the boat, my father had to take off his

sea-boots (gumboots), and he had to hang precariously way out over the stern so he could

unwind and cut the rope off the prop. It was not an easy task out at sea since there was

a protective metal bracket directly in front of the prop, which could not be removed. He

struggled for a good half hour before he got it all cleared up.

Anyway up came the first pot of the day. Nearly all the pots my father used for fishing

were the so-called parlour style pots. He had read about them in the periodical “Fishing

News”, and because of their effectiveness, he had gradually switched nearly all his pots

over to that design. They were D-shaped, covered with hand-woven twine netting, and

they had two compartments. The entrance was into the first compartment where the bait

was hung, and directly adjacent to the bait was a false exit, which led into the second

parlour compartment where the lobsters were trapped. The pots were very effective at

accumulating lobsters over a period of time, and they could be left to fish unattended for

several days. He weighed them heavily with a few bricks to insure they remained in

position in rough seas during a strong gale. We had no winch to assist in the pull up,

just some back muscles and a pair of strong arms. The pot had two nice lobsters

weighing around a pound and a half or so, and they were located as expected inside the

parlour. After opening the twine on the side, my Dad pulled them out, and placed them

temporarily in the opposite corners of the lobster box. The bait in the pot seemed

sufficiently fresh and intact, and while he closed off the side, I circled the boat back

around towards its original position. He dropped the pot over the side and threw the

buoy and rope clear. The sea was quite deep in the area. The bottom was not visible,

and no attempt was made to try and precisely locate the pot. He grabbed a couple of thin

bicycle wheel inner-tube strips, which he kept in a can nearby. He sat down, placed the

lobsters one at a time between his knees, and quickly tied their claws shut with the inner-

tube strips. He then placed them back in the lobster box, and covered them with a layer

of wet seaweed. Then we were on to the next buoy. This pot had a large male crab.

Dad indicated the crab must have got into the pot early since there was nothing else

present. Once the pot was occupied with a large male crab, a lobster would not dare

enter. The male crab has an enormously powerful set of claws with

oversized ‘forearms’ making it a very formidable competitor. He pulled the crab out by

its rear legs and placed it on the bottom boards. The crab slowly crawled over to an out-

of-the-way corner under the seat and settled there with bubbles emanating from the front

of its shell, a survival instinct it seems for large crabs out of water. He replaced the bait

in the pot since it had been mangled up pretty badly, and what was left was rather putrid.

The third pot had a large spotted dogfish similar to the one I had caught off Nefyn Point a

few weeks earlier. It was around three and a half feet long, and was the larger cousin of

the dogfish caught on the long-line. It had really contortioned itself to get into the

parlour area, but had not damaged anything in the pot. It was still alive, and it went

straight into the bait box. We completed the fishing and re-baiting of another six pots

off Gorllwyn, picking up another three lobsters in the process. One was a three to four

pound beauty with huge claws. Like many of the large lobsters found in those days, it

was covered in barnacles – a distinguished feature of age and maturity in the lobster

world.

Large Spotted Dogfish caught by the author in a parlour pot on Nefyn Point in June 1953.

(Click photo to enlarge)

My father took a quick breather as we slowly headed across the Bay towards the next

group of pots off Carreg y Llam (Bird Rock). We passed the coaster on the shore side

on the return trip. There was still no activity on board. Viewed from that northerly

direction and close in-shore, it was always a shock to see how much of the Carreg y

Llam headland had been excavated by the quarrying. The hole on that northerly side of

the Rock was just massive. Nearly a quarter of the headland had been removed at two

distinct levels near the top. None of the damage was visible from the Nefyn side. The

headland appeared quite natural from the Nefyn side, but the Rock was deceivingly only

a thin shell at the highest quarry level near the top. Granite was a local resource in the

late nineteenth century, and while quarrying was fully understandable providing for the

wide employment of men in the area, it severely disfigured the landscape. The Trefor

side of the Rival Mountains is even more grotesquely scarred. Nothing can be done to

backfill those quarried levels. But the most objectionable parts are usually the slag heaps

of discarded granite that radiate out below the lowest quarry levels. I suppose the slag

heaps will re-cover slowly with time. It took us around fifteen minutes to reach the front

side of Carreg y Llam. That side of this huge Rock was just fascinating. The whole

area around it was thriving with wildlife. The variety of sea birds on the rock face was

amazing with gulls, petrels, and terns of all kind. There was a small group of puffins

on the grassy slopes near the southern end of the Rock, and even the rare red-billed

chough had been spotted there on occasions. The noise the birds made was deafening.

The chicks were nearly fully-grown at that time of year, and they scrambled all over the

rocky ledges adding to the noisy staccato as the boat pulled in. We had to get up close

since the most lucrative lobster fishing areas were right up against the edge. I always

had some trepidation about being that close to the rock face, which towered vertically up

above the boat. I was always conscious of that thin shell at the very top. The workers

dynamited granite in the quarry every day at exactly twelve noon and you could clearly

hear the explosion all the way from Nefyn beach. What if some rocks worked loose

when they blasted at that highest level? The boat below would not have a chance if the

rocks suddenly dislodged and came crashing down into the sea!!

While my father was pulling in the first pot off Carreg y Llam, I was loudly clapping my

hands to induce hundreds of birds to fly off the cliff face. “Clap your hands but don’t

look up”, was the advice given to English visitors brought by boats to the area. The

birds showered everyone with goodies. That is probably what kept the sea-life around

the Rock so vibrant!! We just kept on fishing. This pot was not a parlour pot but a

traditional so-called Aberdaron style pot with just one compartment. He had around six

of those still left from the earlier days. They were made of woven willow saplings, and

were spherical in shape with the entrance at the top. These pots had the advantage of

being more durable in heavy seas because of their rounded configuration. They were the

pots of choice in the Aberdaron area where the fishing was done in the strong tides and

rough seas around Ynys Enlli (Bardsey Island). But they had to be fished regularly since

the lobsters could get out. This pot had two nice lobsters, so I guess we had pulled it up

just at the right time. My Dad could pull the lobsters out and re-bait the pot by putting

his arm through the large entrance. I picked up on my father’s hand signals to circle the

motorboat back and around. The noise level from the birds was so loud you just could

not hear a thing. When we were close to the original position, over the side went the

pot with the rope and buoy again thrown clear. He pointed out the next green and

yellow buoy a few yards away. I took my time to get to this one to give him time to

claw tie the lobsters. This pot was an Aberdaron style too, and it had another nice

lobster in it. The lobster had a gorgeous light blue shell coloring, an indication that it had

recently grown a new shell after casting off the old one. That’s how lobsters mate and

grow in size. They find protective holes in the rocks to safely moult off the old shell and

gain time for the new larger shell to harden. Crabs go through the same procedure.

They are usually found in holes in pairs, the male lobster having induced the female into

his den. The male mates with the female after she has shed her shell and then provides

protection while the female’s shell hardens. The lobster’s new shell is a nice light blue

color before it hardens and turns a darker blue. The light blue colour was much more

prevalent amongst the younger lobsters since they moulted their shells a couple of times

a year. The older lobsters moulted much less often, and that gave time for barnacles to

attach and build up on their shells. My wife Nancy keeps telling me that I am

accumulating barnacles at a rapid pace!!

It was in those holes that we would catch lobsters and crabs in Creigiau Mawr on Nefyn

beach. The trips to the Creigiau Mawr rocks during the low spring tides with my father

were one of my earliest exciting recollections. I would scramble over the rocks after

him as he visited the various holes. The holes had been there for years, and were known

by most of the lobster fishermen. Like most things in Wales, each hole had a name, and

my Dad’s favourite was called the ‘Rhigol’. It was his favourite because he caught a

huge lobster there years earlier, a lobster that seemed to grow bigger in size every time

the ‘Rhigol’ story was told!! The most productive holes were on an island off the

seaward end of the rocks, which was only visible and accessible during the low spring

tides. The island had three lobster holes and two crab holes (the crab holes were not as

deep), and he would catch lobsters and crabs there quite frequently. The island was

accessible by walking over a submerged ridge with deep water on either side, and as a

toddler he would make it very clear that I was not to follow him there. Fishing on the

island was restricted to around one half hour due to the oncoming tide, so he had to be

fairly quick. The lobster holes there were submerged in a couple of feet of water. The

occupying lobster would methodically clean out the hole, and the first indication of its

presence would be a pile of sand outside the entrance. It would sometime be also sitting

right at the entrance with just its claws and feelers in view. The procedure for removal

was to carefully slide a long rod past the lobster into the hole making sure not to contact

those feelers. The rod was bent at the end, and rotating the rod caused a disturbance at

the back end of the hole. The lobster would then turn around to defend itself against a

perceived attack from the rear, and in a few minutes with a simple flap of its tail, it would

shoot out of the hole backwards where it would be quickly grabbed. The crab was

much more lethargic and could be easily pulled out of the hole by hand. As the three

boys in the family grew up, we quickly learned the location of those holes, and

we ‘crabbed’ in the rocks quite often. My favourite lobster hole was ‘carreg fflat’, a

large flat blue colored rock located on the eastern side of Creigiau Mawr just north of the

mooring area. I caught a couple of nice lobsters there. The crab and lobster catches

from the rocks would always be brought home for dinner.

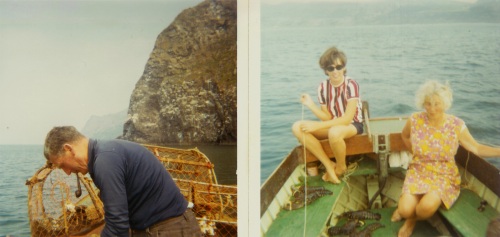

My father Lawrence Owen, my mother Maggie, and my wife Nancy lobster fishing off Bird Rock in 1970 - watch your feet!!

(Click photo to enlarge)

Anyway back to Carreg y Llam. I nudged my Dad and pointed out the grey seal that had

surfaced at the entrance of the nearby cave close to our next buoy. There was a small

colony of seals living in the area and they were often visible around that cave. There

was a ledge near the cave entrance, and from the right viewing angle you would often see

a seal perched right on the ledge. The seal quickly disappeared as the boat approached.

This pot was an Aberdaron style as well. Dad seemed to have all the Aberdaron pots

located just off the face of the Rock. The pot was empty except for a large starfish, and

the bait was gone. He pulled out the starfish, re-baited the pot, and moved it a few yards

away from the cave entrance. The starfish was really neat with five symmetrical arms,

and I flipped it on its back to see if it could turn itself over. The next pot was a parlour

style and it had one lobster and a nice large female crab. The female crab does not have

those obscenely large claws and ‘forearms’ like its male counterpart. By this time we

were close to the large and separate flat rock, which sits at the southern end of Carreg y

Llam. The official name for this rock apparently is Llech Lydan (Wide Slate), and it

sits around thirty feet out of the water. This was home to a large colony of guillemots

and cormorants. The cormorants had their wings outstretched, drying their feathers like

vultures in the early morning sunlight. They did not move as we approached, probably

because their chicks were close by, but some of the more nervous younger guillemots

dived in the water. Both birds are very agile underwater swimmers, and the cormorants

in particular can stay under the surface for several minutes. It was not uncommon in

this area for a cormorant to target the bait in a lobster pot, with disastrous consequences.

The bird would swim around, locate the entrance, get into the pot, and then would drown

trapped on the inside.

There were another five pots distributed around the front of the Lech Lydan rock, and

they were all parlour pots. We picked up a further two lobsters from those pots. It

was in this Bae Pistyll corner of Bird Rock that the solitary fisherman would experience

the most difficulties. The prevailing winds in the Irish Sea are from the southwest, and

they blow directly into the corner. The sea is shallow in the area and close to the Llech

Lydan rock the waters get very choppy even in moderate winds. This is due not only to

the incoming waves but also due to the backwash from the rock. It was difficult to keep

the boat under control and pull up the pots at the same time. The exact winds strength

and direction were very important parameters. The worst-case scenario was a gale force

wind from the northwest. Fishing in the rain was not an issue since that required only

an oilskin and a sou’wester. My father listened very carefully to the BBC shipping

forecasts for the coastal areas of Britain. The forecasts were on the radio so often at

home that I could recite the coastal area listings quite accurately as a toddler. The only

area I would mispronounce apparently was ‘Heligoland’. Dad relied totally on those

forecasts for planning his trips, and he never took chances if there was any doubt. Those

were the days of course before televisions existed in Nefyn, and certainly before weather

maps, GPS systems, mobile phones, boat to shore radios etc. were available to everyone.

Anyway, we were in Bae Pistyll (Pistyll Bay). There was always a sense of sadness

after pulling up the last pot and it was time to finally leave Bird Rock. The place was

very alluring, mesmerizing and full of action especially for a twelve year old. Even

the visitors brought there by boat would always ask for one more spin around before

departing. Then we were off heading across Bae Pistyll towards Bodeilias Point. There

was a person walking through the fields above the cliffs half way across the bay. The

fields were part of Pistyll Farm, and the farm only kept sheep in those fields. The fields

were very popular for mushroom picking, and that’s what the person seemed to be doing

since he stooped over periodically. The Plas Pistyll Hotel on the Nefyn to Caernarfon

road was located close to the shoreline, and there was some activity outside the hotel.

That was to be expected since it was now nearly seven thirty in the morning, and most of

the guests were up and having breakfast. My father continued the task of tying the claws

of all the lobsters, and multi-layering them between the wet seaweed so they were ready

for the keeping pot. The starfish had not made an effort to turn over so I threw it back

over the side. While steering the boat, I had one more go with a spinner line and picked

up another two mackerel as we crossed the bay.

The small headland of Bodeilias Point now in front of the boat was also grossly

disfigured from quarrying. Apparently a small company owned by the nearby Ty

Mawr farm started the quarry around 1860. They constructed a dock on the headland

so coasters could pull in at high tide and be loaded up with granite. The quarry closed

for business in 1906, and the headland was left with a two-level, stepped profile. The

headland appears in the forefront of all the scenic postcard photographs of the Rival

Mountains and Bird Rock taken over the years from Nefyn Bay. I have often wondered

whether any photographs of that scene were ever taken before the headland was so

grossly disfigured – there were cameras around at that time. And more significantly,

what did the original headland look like? No doubt the early workers who built the large

sailing ships on Nefyn beach in the mid nineteenth century saw a different view than we

are used to. Perhaps no photographs of that scene were ever taken, and we shall never

know.

We caught another lobster and three crabs in the pots off Bodeilias Point resulting in a

respectable total catch of twelve lobsters and five crabs for the day. Before pulling in

at the moorings, my father decided to re-lay the long-line in readiness for the following

morning. It was much easier to set the long-line than to pull it up. He laid it out in an

orderly manner along the inner side of the boat, baited the hooks with mackerel strips,

and hung those hooks out over the side. It was easy then to pay out the line slowly as the

boat drifted with the tide.

We were back in the mooring area unloading the lobsters into the keeping pot at around

nine o’clock in the morning. The hand-lines were put away, the boat was washed down,

the bilges were pumped dry, and the weather cover was put back on the boat. The five

crabs were taken home for dinner together with around eighty mackerel.

Dr. Brian Owen

Emmaus, PA, USA

Top of Page