NEFYN BEACH CABIN CRUISER

May 2020

A recent photo showing damage to huts on Nefyn Beach due to storm Ellen reminded me of damage from a similar storm that occurred around the mid 1950's, over sixty years ago when I was growing up in Nefyn. That storm also occurred in August and it not only damaged beach huts but also some rowing boats, motorboats and it totally demolished a large cabin cruiser.

Cabin cruiser type powerboats are fairly common nowadays all over the world. They were certainly not common in Nefyn on the Lleyn Peninsula in Wales in the mid 1950's. The cruiser arrived in Nefyn Bay from the direction of Porthdinllaen a couple of weeks before the storm. It made a majestic entry into the Bay. The boat was white in color with an abundance of mahogany on its superstructure and flying a couple of union jack flags, angled appropriately over the stern. It was towing a small rowing boat. It made a wide circle around the bay before dropping anchor inside the motorboat mooring area. It looked as if it had arrived fresh from a gala yacht celebration in Portsmouth, fully expecting the Nefyn brass band to be there playing Rule Britannia on the beach. Everyone was staring in adoration at the cruiser as if Princess Margaret was going to make an appearance on it. The boat was wooden, built by Chris-Craft and was about twenty five feet long with a wide beam and an inboard engine. The owners used the small boat to come ashore.

Just like today, the motorboats were all moored outside the Creigiau Bach breakwater, and most of them were owned by Nefyn fishermen and residents. Since the local boys rowed frequently back and forth to their boats in the bay, they had quickly assessed the main features on the cabin cruiser. It had an elevated deck with a step up on one side to a central fly bridge and a step down on the other side to a cabin area containing at least a table and seats. There were windows around the bridge for good vision and portholes on the sides of the cabin. The decking on the boat was also mahogany. No doubt, it had some live - aboard amenities suitable for a couple of people or a small family.

In those days, it was customary for a visiting boat to sail to a destination, rather than being driven there towed on a trailer behind a car. And Nefyn together with Porthdinllaen were the only boat destination stops on the north coast of Lleyn. There were no mooring codes or regulations in Nefyn and a boat could drop anchor anywhere in the bay. The local fishermen however had rules among themselves on the safest places for anchoring and how the moorings for the boats should be structured. Small rowing boats were always moored with a front and stern anchor on the soft sand inside the Creigiau Bach breakwater. An anchor on both ends prevented the boats from moving around and crashing into one another. The soft sand cushioned the keel impacts the boats received in heavy surf. The boats were the robust, well-built, old-fashioned clinker-type designs, not likely to be damaged anyway and very solid and stable in rough seas.

The motorboats likewise were nearly all clinker-built. They were anchored on set moorings outside the breakwater so they were floating at all stages of the tide and partially sheltered by Creigiau Mawr. The basic design of the moorings and their layout within that area had evolved among Nefyn fishermen over decades of secure boating. The moorings were set out at very low water in the springtime. I helped my father set a few on several occasions in April or early May. Each consisted of a heavy ground chain thirty feet or so long with a large anchor at each end and with the boat attached to the center of the ground chain via a swiveled bridle chain. The bridle chain was attached to a rope and buoy on the surface. The anchors and ground chain were laid out fully stretched along the seabed in a northwest-southeast direction so as to handle the more dangerous northerly and northwesterly gales. The northwest anchor had a small buoy attached to it which was only visible at low water. This helped pull up the mooring for servicing periodically but it also helped others in setting the moorings parallel to one another. They were roughly in three groups of eight or so, to accommodate as many motorboats as possible. More could be added at the eastern end of the area but they would start losing shelter and be in more open water. A boat would tie up to a mooring by pulling up the buoy and rope and securing the bridle through a metal cleat to an anchor post on the boat deck. The bridle was tightened appropriately, dependent on the stage of the tide. The basic idea was for the bridle's pull on the ground chain, anchored at each end, to act as a spring to counter the effect of the waves while keeping the boat appropriately spaced from the others.

The cabin cruiser was a nice looking boat and it received almost continuous attention from people on shore. I did not know the people who owned it, but I noticed people swimming off the transom at the stern and having a good time. They went back and forth to shore with the small boat via the main slipway at Creigiau Mawr and they were aware of the attention their cabin cruiser was receiving. The weather was nice and calm when the boat arrived and they took several trips down towards Bird Rock and Gorllwyn the following days. It was not a power boat in today's sense with multi powerful outboards, but its internal engine and single propeller was sufficient to move it along at a good speed. What impressed me most was the way the boat cut through the water and the wake it left behind, a well designed boat for sure. Most visiting boat owners would inquire about renting a mooring or have someone local lay one for them. These owners did not do that apparently and they kept the cabin cruiser tied up on a solitary anchor among the other motorboats in the bay. I am sure it was a decision they later regretted.

I was a teenager on holidays from Pwllheli Grammar School and spending time hiring out my father's rowing boats to English visitors on the beach. There were other local boys doing the same thing, Dafydd Hughes and his late brother John Parry and also the late William John Hughes and his brother Robin. We boys moved up and down the beach with the tide and with our boats in the shallows at the waters edge, ready for any interested customers. We were busy all day and when the day was over, we would get the anchors out and park the rowing boats overnight on the soft sand inside the breakwater. When I came up from the beach on the day before the storm, my father asked about the cabin cruiser and how far away it was anchored from our smaller motorboat. He expressed concern since a strong northwesterly gale was forecast for the Irish Sea later that evening and the spring tide was set for its highest level the following day. A large spring tide with rolling waves meant the sea would surge within a few feet of the base of the cliffs all along the beach when the tide was fully in around midnight. This was not good news for the proprietor of the cafe at the bottom of Screw Road who owned the beach huts and who was also a fellow fishermen. I reassured my father that all was fine. Our motorboat was well away from the big one and all five of our rowing boats were anchored securely on the inside of Creigiau Bach.

He woke me up real early the following morning and asked me to go down the beach and check on everything. He was concerned. He had checked the barometer, the glass as he called it, by the front door and the atmospheric pressure was the lowest he had seen in a while and it was still falling. Dawn was about to break and the wind was howling as I left the house in Glan y Pwll. I remember struggling against the strong chilling headwind as I crossed the field from Tyn Pwll Lane on to the edge of the cliff path. Just before I stepped down the embedded slate steps to the path below, I held on to the adjacent fence post for a couple of minutes to review the scene. The sea was raging out there with waves breaking white way outside Nefyn Point and running in a white continuum all the way in to the shore line. The tide was just inside the Creigiau Bach breakwater and coming in fast. Everything seemed okay among the motorboats but several of the rowing boats were swamped with water in the soft sand and were not where they were supposed to be. Clearly, the storm had done some damage at high tide the previous evening. As I went down the path into the corner, the enormity of the damage became more obvious. A large number of the huts were scattered in pieces across the sand near Carreg Frech and many others had collapsed on their spot. There were belongings scattered everywhere along the waters edge. Some people were already in attendance lifting pieces of the huts on to the bottom of Screw Road and dismantling others and raising them off the sand on to the cliffs. There was no wall on the cliff edge in those days and none of the huts were elevated on stilts as they are now.

Two local fishermen, Meirion and Dic Jones (Dicw), were already on the beach tending the rowing boats. I had noticed their bicycles parked on the cliff path. I hurried over to our shed to get my sea-boots on and joined them on the sand. We tipped over some of the lighter boats that were full of water and then left them upside down. We used buckets to bail out the other heavier boats so we could access their drain plugs to drain the rest of the water out. The idea was to get them ready to drag off the sand to safety before the tide was fully in. We collected the stern anchors and ropes that we had access to and piled them up on the side of the slipways. It was hard and exhilarating work but it was impossible not to get wet from the water, the wet sand and the close by whipped-up surf. We had to be careful as well. The gale was blowing in extraordinarily powerful gusts and one gust was sufficiently strong to upend one of Dicw's boats that we had just turned over. It was an unbelievable gale.

More locals came down to join in and help including Dafydd, Wil John and his brother Robin, Gwilym Maes, and Dick Pant. With all that help, and quite a few visitors joining in, we dragged all the rowing boats, including ours, off the soft sand up the slipways to the fishermen areas in front of Penogfa, or between Penogfa and Hen Dafarn, or up the slipway beyond Hafod y Mor to the grassy area where the fishermen dried their nets. Everyone worked together and helped each other in those days. The task did not take long but our major challenge was dragging two specific boats named La Margueritta belonging to Meirion and Snark belonging to Dicw. They had their own anchoring spots just off the soft sand because they were so incredibly heavy. It was still a struggle to drag them and it took many rest stops along the way before we got the boats to safety on dry land.

When we were done, I left my sea-boots in our shed and hurried home for some breakfast. I then ran down to Nefyn where my father was working in the Post Office to reassure him that all was well before I headed back down the beach. The wind had now changed direction, coming straight from the north, and blowing parallel to the headland directly into the bay. It had not abated one iota as I ran down Screw Road past pieces of huts leaning against the wall at the lower end of the road. There were deckchairs and personal property from the huts still scattered on the sand. I noticed that the cabin cruiser was lower in the water as it rode the breaking waves in the bay and it seemed to be dragging its anchor. By now the tide was flooding over the soft sand where we had earlier dragged the rowing boats. The breakers were crashing ferociously into and over the Creigiau Bach breakwater.

I joined a group of fishermen in front of our shed and watched in disbelief as the scene slowly unfolded towards mid-day. The cabin cruiser was taking on water and sinking lower and lower and with the added weight, it was dragging its anchor right through the moorings of the other motorboats. Someone indicated that the owners had got off the cabin cruiser using the small boat the previous evening before the storm got too intense, thank goodness. The boat's bow still pointed into the sea, which was good, but the crashing waves were depositing more and more water into it. It was moving faster and faster towards the partially submerged boulders within the breakwater. We were in shock watching but there was nothing that we could do to alleviate the situation, and the inevitable was coming. The stern of the boat hit the breakwater with a crash, just where the boulders were slightly above water. Each wave seemed to lift the boats rear end further up and over the boulders while the boats bottom was slowly being ripped off. The boat was coming apart before our eyes, I could not believe it. As each wave came over the bridge, the water poured out of its sides as another wave came crashing in to repeat the process again and again. It took half an hour for the boats top superstructure to be smashed right off and deposited on the other side of Creigiau Bach while the main cabin body with its keel and attached engine was forced slowly through the breakwater. Sections of the sides and decking were breaking loose, some caught in the boulders and others floated back and forth in the surf inside the breakwater. People were dragging the bigger pieces on to slip area by the old well. Bits and pieces and personal property from inside were trashed and scattered everywhere along the wall in front of Penogfa and the cottages.

I had no camera at the time but wished I had. Perhaps I would have been too shocked to take photos anyway. It was an unbelievable sequence of events to watch the ferocity of the gale trashing the boat mercilessly to pieces on the breakwater. I will never forget it, “bythgofiadwy” as they say in Welsh. It made you respect the power of the sea and how helpless people must have felt, two bays down the coast west of Nefyn, where the steamer Cyprian came ashore on rocks in 1881. People viewing from the shore then could do very little as nineteen lives were lost.

The bathing huts along the cliff edge received another onslaught from the high tide waves and many more were damaged. The anchor dragging through the mooring area had caused other motorboats to crash into each other with one sinking and awash in the bay. Another two came free of their moorings and came ashore away from boulders and rocks further down the beach. Those boats were damaged but not to a major extent. The remnants of the cabin cruiser remained on the inner side of the breakwater for a few weeks after, so it could be inspected for insurance purposes. The conclusions among the local fishermen was that the boat was simply not moored correctly. Someone came down from the Red Garage in Nefyn later to remove and try to salvage the engine.

The cabin cruiser that came around Nefyn Point in all its majestic glory less than a month earlier, left Nefyn in several dump truck loads shattered to pieces. I doubt if the owners ever returned to the area. It was the worst Nefyn storm I experienced and one that I will never forget.

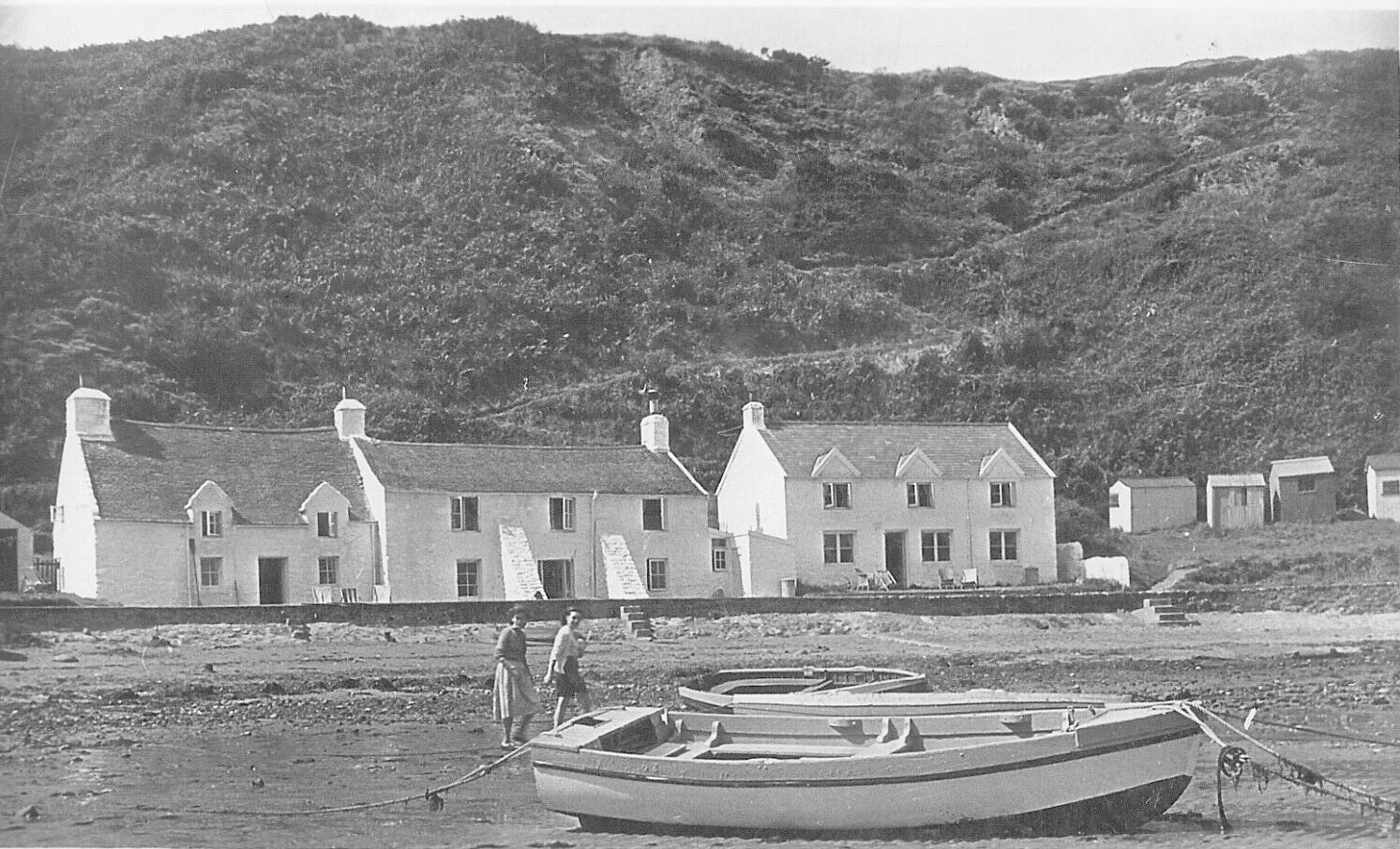

A 1950's photo of Nefyn Bay showing the old Creigiau Bach breakwater. Motorboats were moored outside the sailing boat on the right and rowing boats were moored on the sand and in the area they are shown in the photo. Some beach huts are also shown along the base of the cliff.

(Click photo to enlarge)

A 1950's photo showing the breakwater almost totally submerged at high water in a large spring tide. In the storm, the cabin cruiser came over the breakwater near its center where the solitary boulder just breaks the surface above the rowing boat in the photo.

(Click photo to enlarge)

A 1950's photo, not with the highest of tides, showing a decent northwesterly storm with heavy seas over the Creigiau Bach breakwater.

(Click photo to enlarge)

A 1950's photo of Dicw's heavy rowing boat the Snark anchored on the beach.

(Click photo to enlarge)

A 1950's photo showing the size of the boulders within the breakwater. It also shows my brother Mike at the waters edge hiring rowing boats to visitors and Meirion's heavy boat the La Margueritta (front center behind the two boys).

(Click photo to enlarge)

Dr. Brian Owen

Emmaus, PA, USA

Top of Page